Editor’s Note: This is the first profile in what will hopefully become a growing archive of our customer experiences with building boats. This inaugural post is from Mike Birke in San Antonio, Texas.

After having two kayaks and one canoe under my belt I felt it was time for a change. Looking at my options, and given my limitations with tow vehicle and garage space for building, I saw two possibilities: a small sail boat or a small motorboat. Although a sailboat seemed like a great idea, I had to look at the primary reason for making another boat, besides having something to do of course. Since my wife and I love to fish down at the coast, and the wind is a constant companion, we are limited to how far we can paddle out to get to the fish. It would really be nice to be able to get out further in the bays and explore all of the shallow lakes and other fishing spots that are currently out of reach.

Although I started out in a sea kayak, which is great for paddling, it really isn’t the best thing for fishing, especially with the muddy bottoms that one encounters around Port Aransas and the Light House Trails area. That led to canoe, which is great for fishing, but quite susceptible to cross winds. And in the spring time, when the winds howl at what seems to be hurricane speeds, it severely limits our nautical range. We still use the canoe frequently on lakes and rivers, but for the coast, something else was in order. Enter the search for a small motor boat. My requirements were as follows: 1) Either lapstrake or glued lap strake design. 2) Ability to handle up to a 10 hp motor. 3) Light enough to be towed by my vehicle (4-banger truck) 4) Flat bottom for fishing the shallows of the Texas coast (although I really like the way a V-bottom looks, it just isn’t practical for my intended use) 5) Plain old good looks.

I spent a few weeks looking at various designs, and finally decided on David Nichol’s Lutra Laker. It satisfies my requirements and has a few bonus features, the most notable one being a raised platform on the front to fish from. The other feature being several water tight storage areas at the bow, stern, and amidships. Although I don’t plan on stuffing sleeping bags and gear in these compartments for overnight camping trips or the like, I like the safety floatation aspect that these offer. I never realized how important this quality is until the first day I took my canoe out and intentionally dumped it (near the shore of course). Long story short, if I would have tried to flip it back over from the turtle configuration, it would have sunk. That little sea trial really opened my eyes and brought safety back to the forefront of my thinking. Keep in mind, we always wear our PDFs when out in the kayaks or canoes, but to know that the canoe, once flipped has to be towed back to shore upside down before we could upright it was disturbing to me. There are those out there who may be able to flip it back over in deep water, but I ain’t one of them. Anyhow…I digress… back to the Laker…

I wanted to talk to David about whether a feller like me could put one of them there boats together without any glued lapstrake experience. David assured me that between the video, plans, online, and phone support, that I wouldn’t have any problem. So I asked my wife if I could have an advance on my allowance to purchase plans and materials. My advance was granted and I was off and running! The plans arrived a few days later with the materials list. I ordered all the epoxy, glass, and miscellaneous materials on line and made a quick trip to Houston (I live in San Antonio) to get the BS 1088 Okoume plywood (the stuff is absolutely beautiful by the way). The first order of business was lofting, which I had heard of, but never tried, and I soon found out that the hardest part of it was switching the brain into the “lofting” mode of feet, inches, and eighths. I have wondered why this convention is used instead of what I call plain old measurements, and I’m sure someone smarter than me, somewhere came up with it.

Anyway, after one form I was in full lofting mode and quickly completed all eight forms on 3/4″ particle board. The transom was lofted on to 9mm ply. The sawdust was flying from my circular saw soon thereafter and before I knew it I had a nice stack of forms. On to the next step… the strong back. Since I already had one from the other boats, I just had to reassemble it. That’s when I found out it was a foot and half too short, so I cobbled an extension together and screwed her on, bringing it to proper length. Then I marked off my form measurements and began assembling all of the forms on to the strong back. I wanted everything mounted, and leveled so I could use my eyeball to see if I had made any errors in the lofting process. It appears I had everything right, so the next move was to start cutting out the knees and bulkheads. With height measurements garnered from the plans, I temporarily nailed the 6 mm ply to the forms and, per the instructions, used a router with a flush cut bit to cut the forms out. I used a 1 _” hole saw to cut out a “mouse hole” for the water to drain through.

The next step was lofting the stem on scrap ply to make a template. Then I temporarily mounted it to do another eyeball measurement. Things looked good there, so I epoxied two 9mm scrap pieces together for the final stem. Once dry, I traced the template and cut out the final product. In addition, per the instructions, I put a bevel on the sides using my trusty Shintu rasp. Beveling the stem will allow the planking to lie flush against it. I also left about a quarter inch flat on the leading edge. For the final mounting, the temporary vertical mounting form was cut short of the where the garboard mounts to the stem.

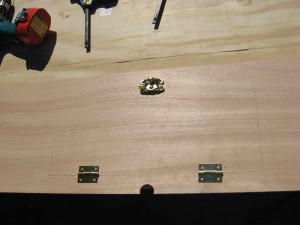

Along side of this process, I was also putting the transom unit together. Form 8 has two braces mounted via cleats, epoxy fillets, and tape. These braces are also glued to the transom in the same manner, and they also set the angle of the transom. The exact angle escapes me, but as suspected, the transom angles towards the front of the boat from top to bottom as viewed from the side. With the transom mounted it is now time to start splicing the 9mm ply together to form the bottom.

Although David is a fan of using the belt sander method as shown in his video, I am trying a method that uses a jig and circular saw. The jury is still out on the effectiveness of this technique. I did find out though on the first few tries that my jig guide strip was too deep, causing the body of the saw to rock on it, naturally resulting in a wavy cut. Right now the strip is _” deep, so I plan on knocking it down to about 3/8″. With the problem identified, I look forward to making the necessary adjustments on my jig this weekend and taking another shot at this splicing stuff. I’ll let you know how things turn out.